Summary:

Processing feedback goes far beyond listening to it in the moment and implementing it; it involves continuous reflection, conversation, and practice. While much of this happens because of the way we receive feedback, there is much we can do, too, to make sure we’re processing feedback the right way.

As an English major, writing was a big part of my curriculum. Whether I was writing literary criticism or a reflection on one of Shakespeare’s sonnets, my papers rarely came back to me with clean white margins. But there was never any formal feedback. The edits just meant the professor had wrestled with my writing and that I had plenty of opportunities to learn. I eventually grew accustomed to seeing my work covered in red pen. As I entered my senior year, however, self-doubt kicked in. Was I good enough to be a writer? Did I have what it took to pursue a master’s degree in writing?

While in the throes of doubt, a professor asked me to swing by his office. “This poem you wrote,” he said, trailing off. Time slowed in that moment of his brief pause, and I remember holding my breath and wondering if I had offended him or made some mistake that he had corrected before. “It’s special. Do you see what you did here with this line break? This is the move of a seasoned poet and I want to make sure you understand why.” He went on.

Though I had listened to this professor’s feedback, it took years for me to realize that I had processed this feedback better than any other I’d received. First, it was specifically positive rather than vague like “great work.” It wasn’t part of the “feedback sandwich” method, where some professors would layer constructive criticism between what felt like two empty compliments.

Second, the positive feedback included a question that caused me to reflect, which has been shown to foster more learning.

Lastly, it was a conversation. We spoke about that poem for 20 minutes, with the professor showing me examples of other poets who made similar moves. During the conversation, I shared the thinking behind why I used this particular technique — and in talking out loud about it, I came to understand it better.

In time, I’d turned it from a new perspective into a part of my repertoire.

Processing feedback goes far beyond listening to it in the moment and implementing it. It involves continuous reflection, conversation, and practice. Yes, much of this happens because of the way we receive feedback (such as how my professor gave it), but there is much we can do, too, to make sure we’re processing feedback the right way.

Based on my experience, here are six Ps for processing feedback better that I believe can help anyone make the most of the feedback they receive.

Poise

Poise is about holding feedback with neutrality and grace in the moment you receive it. For anybody who has received critical feedback, this is easier said than done. Many of us tie some of our personal identity to our work and receiving feedback can feel like a personal attack, making us want to react. But here, neutrality and grace work in tandem to protect you.

What does this mean in practice? Step into a feedback session with neutrality — neither enthusiastically agreeing with the feedback nor forcefully rejecting it. This approach, in my experience, allows me to be a better listener instead of simply trying to hear the other person with an intent to respond. Also, because I tend to be conflict-averse, this approach usually stops me from wanting to please by showing my agreement (even before I’ve fully understood).

But what if you feel a sense of agreement or disagreement arising within you? That’s fine and natural, but my advice in that moment is to bring awareness to what you’re feeling. There’s no need to act on it yet. If you have questions about the feedback, ask them — but try to do so from that neutral position.

One way to do this is through reflective mirroring, where you restate what the feedback provider said but in a slightly different way. For example, if they say, “You need to get better at delegating tasks more effectively,” you might ask something like: “Okay, what I hear you saying is that you think I’m getting stuck in the weeds and that this is limiting my time to think strategically. Is that correct?”

Process

Avoidance, negative mulling, and immediate acceptance of the feedback usually only prolong processing it and can lead to the feedback’s potential usefulness disintegrating or being held with disdain. This can turn even great feedback into a kind of hardened Play-Doh that is tough to work with.

Processing feedback is about metabolizing it. This demands time, sometimes even a week or more, and doesn’t happen in the moment you receive it. I believe it’s critical to let feedback run through both your body and your mind. That means feeling your feelings and investigating why you may be feeling them.

To practice this, I’ve found it helpful to conjure up the feedback while lying flat on the floor, arms and legs extended. This is also known as savasana, or the corpse pose in yoga, and it helps bring about a state of total awareness and relaxation that calms the nervous system. As you think about the feedback, imagine it literally coursing through your body. What might your body be trying to tell you? Notice if your jaw, fingers, or stomach begin to contract. Notice any changes in your breath and bring attention to those changes.

Keep an open mind and know that tension may not equate to disagreement with the feedback. You may be feeling tense simply because the feedback is spot-on, and you’re feeling a bit embarrassed that you didn’t see it for yourself. The goal is to begin working on your feedback devoid of judgement and emotions.

Positionality

Next, consider the feedback provider’s motives, position, and intent. When I asked my LinkedIn connections for advice on how they process feedback, Eleanor Stribling, a group product manager, said: “We often think of feedback like a mirror on our behavior, but it’s primarily reflecting the needs, values and impressions of the person giving it.”

Ask yourself: Do you believe they genuinely want to help you? Do you trust them? Gaining a better understanding of where the feedback provider is coming from and how you feel about them will help you develop the objective mindset necessary to work with a potential dissonance like great feedback coming from someone you don’t trust.

Percolate

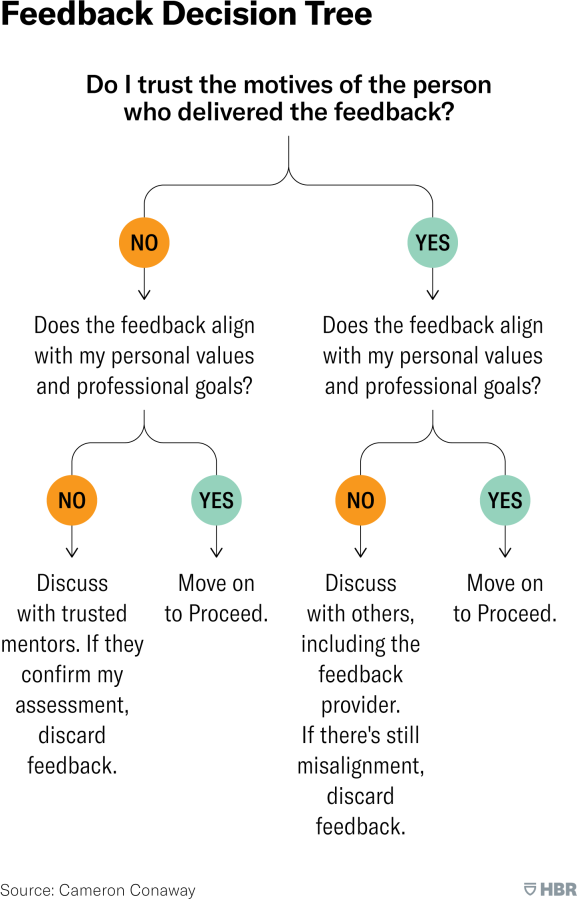

Now run the feedback you received through a simple decision tree — a method to bring consistency and structure to your decision-making process. If you feel all over the place in your thinking, the visual format of a decision tree can help you remain focused as you logically progress through a few critical questions. Mine looks like this:

While the decision tree looks simple, the reflective process that underlies it (understanding personal values and professional goals, for example) often takes some challenging work that is easy to skip. But don’t. Take your time as you work through your thinking. The end result should be that you feel confident in how you will move forward with the feedback you received. If you have decided to accept the feedback, you can move to the next step.

Proceed

Rolling out the feedback all at once usually isn’t the best way. For example, let’s say the feedback you received and chose to implement involves being more assertive in meetings. Let’s say you’ve got six meetings lined up for the day. Rather than going all-in and showcasing this new assertive side of yourself, I’d recommend the “drip” approach — perhaps practicing being more assertive during one meeting that day which is on a topic where you have clear and informed opinions.

Think of it as practice. Mastering a new skill and forming a habit is more likely to happen with consistent practice over a long period rather than jamming six practice sessions into one day. This slower approach can be especially helpful when the feedback you received was constructive but didn’t necessarily come with a guide for how to incorporate it.

Perspective

Perspective is about asking those who you respect and who have seen your new performance what they think of it to ensure there isn’t a mismatch between how we perceive our performance and how it’s landing for others. If the colleague you ask doesn’t know it’s something you’ve been working on, you can frame the question like: “I’ve been working on X. Have you noticed any performance changes in this regard?” If the person does know, you can have a blanket ask: “As you know, I’m working on X. Can you let me know if and when you see improvements in this regard?”

Regarding perspective, I’d also recommend journaling your experience so that you understand how it’s landing with others and how it feels to you. Earlier, I mentioned practicing during one of your six meetings for the day. In this example, it would help to reflect on how that practice went. If your attempt to be more assertive was exhausting because you’re an introvert, capture that in your journal. Over time, you may start to notice patterns and gain a better perspective on how to improve in the ways you want while protecting your energy to stay motivated for the long haul.

Although I prefer to use the order outlined here — poise, process, positionality, percolate, proceed, and perspective — it’s also possible to pursue the six Ps in a different order. You may, for example, already have a sense of the change you want to make. In this case, you could begin directly at percolate, or even proceed, and progress from there.

Lastly, have some fun with this! Not all professional growth must be paired with a formula, but I’ve found it can be a joy to take something relatively abstract like implementing received feedback and looking back over time at how you’ve practiced, how the practice felt, and what new perspectives you’ve gathered along the way.

Copyright 2022 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate.

Topics

Motivate Others

Conflict Management

Collaborative Function

Related

10 Signs of a Toxic Boss — and How to Protect YourselfThe Power of Hidden TeamsDisrupting the Healthcare Status QuoRecommended Reading

Team Building and Teamwork

10 Signs of a Toxic Boss — and How to Protect Yourself

Team Building and Teamwork

The Power of Hidden Teams

Motivations and Thinking Style

Disrupting the Healthcare Status Quo

Motivations and Thinking Style

The Work of Leadership

Problem Solving

Seven Tricky Work Situations, and How to Respond to Them

Problem Solving

The Importance of Mentorship