Summary:

What causes physician burnout, and what can be done to prevent it?

The authors provide a four-stage framework for the foundation of burnout, and several approaches to address it.

ABSTRACT: Burnout is a complex condition that is the result of persistent job stressors and an individual’s response to them. This condition has been described and studied for more than 40 years, and multiple studies suggest physician burnout has reached epidemic rates. This article provides a four-stage framework for the foundation of burnout in practicing physicians and offers several approaches to prevent or reduce its effects.

***

Burnout was first described in the health care industry by a psychiatrist as the experience of emotional depletion and a loss of motivation and commitment.1 Psychologist Herbert J. Freudenberger described people who suffer burnout as “overcome by fatigue and frustration which are usually brought about when a job, a cause, a way of life, or relationship fails to produce the expected reward … usually high achievers who have intense and full schedules, do more than their share on every project they undertake and won’t admit their limitations.”2

It has become a popular topic for study and discussion. A multitude of published works is available on the topic; a recent systematic review identified more than 2,600 articles on the topic,3 and a recent down-to-earth book is available as well.4

But what is burnout? How does it happen? What can we do to recognize it before it develops? And what can we do to prevent it?

Burnout is defined as exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation, usually because of prolonged stress or frustration.5 This term expanded from previous uses in the late 20th century regarding drug culture and rocket engines in the space program. As a psychological syndrome, burnout is characterized as a response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job.6

While there is no consensus on a definition, several factors are consistent in the literature. They include a work stress-related syndrome encompassing emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and a sense of diminished personal accomplishment.3,7

Physician burnout has negative effects on job performance, patient care, physician well-being and even health system success.3,8 Negative effects on patient care include increased medical errors, reduced quality of patient care and lower patient satisfaction. Consequences for physician well-being include reduced work satisfaction, disrupted personal relationships, depression, substance abuse and even suicide. Institutional consequences include reduced productivity, increased job turnover and early retirement of experienced care providers.7

Individual personality traits have been identified that might contribute to the development of burnout. These include Type-A personalities (competition, time-pressured lifestyle, hostility and excessive need for control), low hardiness (involvement, sense of control and openness to change), perfectionism, neuroticism (anxiety, hostility, depression, self-consciousness and vulnerability) and low self-esteem.6,9 While some of these traits are not classically associated with physicians, many are considered both archetypal and representative of physicians and our trainees. A recent article suggested that by swearing to “put the needs of their patients above all else,” the Hippocratic Oath establishes a foundation upon which burnout is a consequence.10

Given the conventional personality traits of a physician, the experience of burnout should not be considered an entirely negative condition. Burnout is a consequence of excessive drive to control, productivity and perfection. Therefore, getting burned out demonstrates that one is committed to being both highly productive and obsessed with high performance. Have you ever seen a low performer get burned out?

Studies indicate between one-third and one-half of physicians are burned out at any given time.11

In a 2016 survey12 of more than 17,000 American physicians:

54 percent rated their morale as “somewhat” or “very” negative about the current state of medicine.

63 percent were “somewhat” or “very” pessimistic about the future of medicine.

49 percent “often” or “always” experience feelings of burnout.

49 percent would not recommend a career in medicine to their children.

58 percent said the least-satisfying aspect of medical practice was too much paperwork and regulation.

70 percent said the Maintenance of Certification process did not accurately assess their clinical abilities.

And there is no timeline for burnout. It is being reported in, and described by, medical students and residents in addition to practicing physicians. In fact, burnout has been observed as a greater risk in early career individuals (under 40 years old).6 Shanafelt, et al., reported young physicians are at higher risk of burnout when compared to their more senior colleagues.13 It also should be recognized that burnout is not unique to physicians and the health care industry.14 The key to managing burnout is to recognize its triggers before it occurs. By recognizing these fundamental components, it is possible to prevent the seemingly inevitable.

Four-Part Foundation

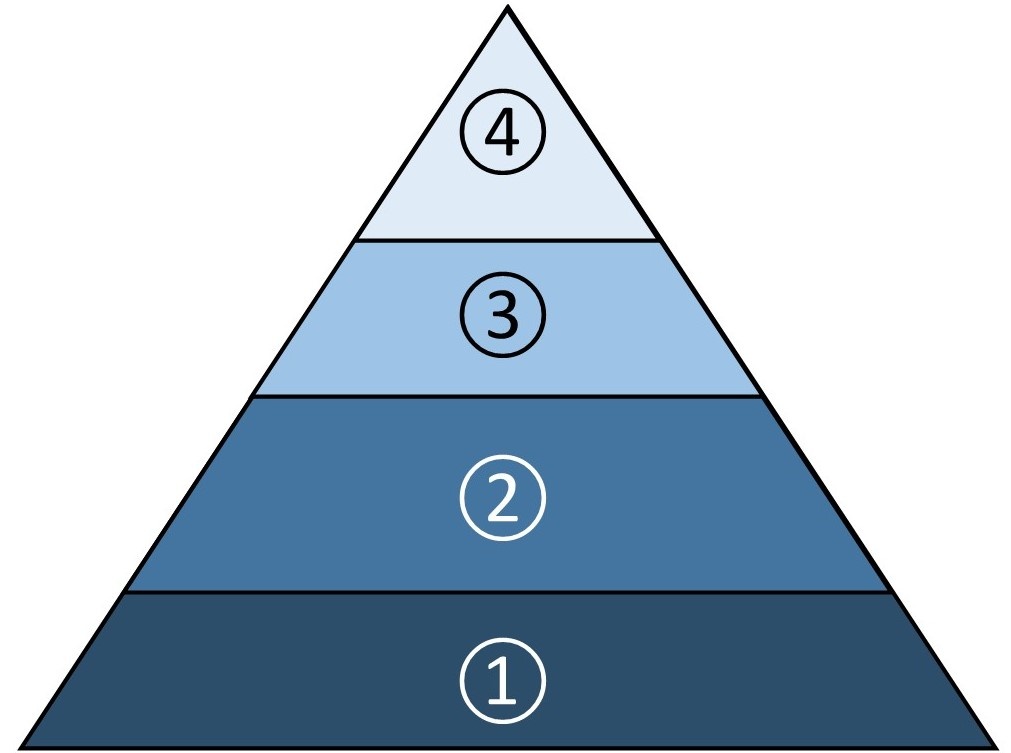

Burnout is built upon a foundation of fatigue, hindrance, frustration and withdrawal (see Figure 1). While there is no preordained itinerary or timetable for burnout to set in, there are a few critical aspects to its development.

FIGURE 1: FRAMEWORK OF BURNOUT

4. Withdrawal: Losing motivation to correct problems.

3. Frustration: Feeling dissatisfied with performance.

2. Hindrance: Feeling surrounded by problems.

1. Fatigue: Feeling overworked and exhausted.

This framework described is typical, but merely illustrative — these elements can develop in series, in parallel or even “out of sequence.” The course taken by an individual is based on his or her personality traits, coping factors, recognition of the stages of burnout, and the availability and use of support systems.

1. FATIGUE — This occurs when demands for time and productivity cannot be met in conjunction with insufficient time for recuperation. It is a response to a combination of physical and emotional exhaustion. This typically occurs when there are more tasks requested than one can accomplish in a given period of time.

For practicing physicians, these tasks manifest as increasing clinical patient loads (revenue-generating) coupled with seemingly unending demands (nonrevenue-generating) that include electronic documentation, patient calls, prior authorizations and regulatory training, to name a few. These demands have extended many workdays to more than 12 hours and have added weekend time to keep up.

The recent concept of "pajama time" has been used to describe electronic record documentation while at home, often at night. The effects of this schedule naturally take a toll. Chronic stress, sleep deprivation and reduced personal time generate an unhealthy work-life balance.

2. HINDRANCE — Physicians are surrounded by seemingly constant impediments to overcome to do our job. Some of these obstacles are formidable, including insufficient support staff and physical space, lack of autonomy, lack of meaningful analytics about one's practice and performance, unattainable budgets, and unsatisfactory communication with administration and leadership.

The concept of “not working to the top of one’s license” often occurs when the physician is left in a position to get things done that do not require medical school and residency training. However, it is important to differentiate between the significant obstacles and the ones (real or perceived) that are trivial but part of medical practice in the 21st century.

Change brings anxiety, and there is resistance among many physicians to accept and acknowledge these changes, which increases anger and subsequent burnout. Considering the personality traits of many physicians, these hindrances — lack of control in one’s field of expertise, not having things done exactly the way one wants, and myriad “seemingly useless” external demands — certainly would affect morale.

One of the underlying personality characteristics that commonly motivate physicians to enter the profession is a need to exert control to avoid feelings of helplessness. One can have near complete control by working in an independent solo practice. Not being in complete control of many workflow tasks is a consequence (and benefit) of a group or employed practice. In this setting, not everyone gets his or her way. Function in a group requires compromise and consensus in place of individual control and autonomy. There’s a clear distinction between autonomy and anarchy.

External demands, such as third-party payer “hoops” (responding to nonclinicians’ determinations of management and treatment), recertification/MOC (which don’t really demonstrate proficiency or expertise in areas of specialization) and regulatory training are atop most physicians’ lists of frustrations. These demands further diminish feelings of control — a phenomenon occasionally described as “death by a thousand cuts.”

3. FRUSTRATION — This occurs when one starts to feel negatively about oneself because of internally perceived reduced quality of performance.

For example, physicians are subjected to increasing numbers of external opinion surveys and comparisons. These surveys measure and compare physicians and their hospitals for patient outcomes, patient satisfaction and more. Ranking physicians against each other on a numeric scale publicly exposes high-performing individuals to lower scores than they probably ever have received in any testing or comparison situation.

It is inevitable that as work demands and stress increase, these high-performing, competitive perfectionists will reach a point where they cannot maintain perfect performance. Unsatisfactory performance can be real or perceived in the eyes of each physician. However, because reality is the perspective of the person doing the perceiving, a physician who perceives his or her performance as suboptimal undoubtedly will feel dissatisfied.

FIGURE 2: CORRECTIVE INTERVENTIONS

Ways to address the stages of burnout.

FATIGUE

Physical: Gym/workout, running, walking, cycling, martial arts, etc.

Emotional: Meditation, mindfulness, reading, hobby, movies or museum.

Time away: Regularly scheduled vacation, disconnected from work.

Demands: Reduced expectations at work.

HINDRANCE

Working to “the top of one’s license.”

Reciting the Serenity Prayer or other inspirational thoughts.

Getting involved in identifying problems and creating solutions.

FRUSTRATION

Improving efficiency: Leverage EMR, improving work flow.

Resetting to reasonable expectations.

Learning about surveys: Use results as feedback for correction.

Remembering we are not invincible or perfect.

Recognizing the new role of physicians in managed and team-based/directed care.

Allowing physicians to grieve for lost control and the heyday of the past.

WITHDRAWAL

Recognizing defense mechanism of depersonalization.

Performance deficits can manifest as mistakes in judgment, decisions, execution, documentation, targets (financial or temporal) or impaired interpersonal communication and relationships. These will result in reduced satisfaction for the provider, patient and those who judge us.

4. WITHDRAWAL — The final stage happens when highly motivated, competitive perfectionists reach their limits in fatigue, hindrance and frustration, and simply give up. No longer caring — or appearing so — is the ultimate escape from perceived helplessness and hopelessness created by physical and emotional demands.

Depersonalization does not resolve fatigue, hindrance or frustration. It facilitates a downward spiral in performance, mood and behavior. And their effects increase until withdrawal is complete (see Figure 2).

Resolving Fatigue

Burnout is fundamentally a response to organizational culture and work environment.15 To properly address this syndrome, interventions must be made at both the individual and institutional level.16 A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce burnout in physicians demonstrated no definitive recommendations, in part because of the wide variation of interventions. However, on the whole, organization-directed interventions had greater effectiveness than physician-based interventions.7

The most effective organizational interventions combine structural changes, interdisciplinary communication and a sense of teamwork and control.17 Contrary to expectations, physician-directed interventions such as mindfulness, communication or education demonstrated only slight reduction in burnout. These findings validate the premise that burnout is fundamentally related to organizational practices and culture.7 In light of the serious negative effects of burnout on patients, physicians and organization, what can be done to prevent the development of burnout? There are a variety of techniques that can alleviate the stages of burnout. As with any other condition we address in health care, the first step (and the most important step in prevention) is recognition of these factors by the individual and someone who can support them, and a willingness to take necessary corrective actions.

Several approaches can reduce physical and emotional fatigue. Rest and high-quality personal time are essential in combating fatigue. Schedule time every week to decompress and clear the mind. This can be accomplished through physical activities such as time at the gym, running, walking, cycling, yoga or martial arts, to name a few. Others include meditation, mindfulness, reading for pleasure, developing a hobby, going to the movies or spending time in a museum. These activities can be pursued alone; however, when combined with a partner, family members or friends, the social interaction can enhance the restful nature of these activities.

Another essential approach to reduce fatigue is time away from work. Regularly scheduled vacation time helps reduce fatigue by allowing the mind and body a break from the daily grind. This is most beneficial when the time is truly away and unconnected. Don’t check email. Don’t catch up on work. An additional benefit of regularly scheduled vacation time is the positive feeling one gets by "looking forward" to time away. To take advantage of the combined benefits of being away and looking forward to being away, schedule vacation time regularly throughout the year. It should be obvious, but one or two weeks away every three to four months provides more sustained benefit throughout the year than a single three- to four-week vacation.

One positive effect of reducing and eliminating fatigue is enhanced efficiency and effectiveness when one returns to work rested and relaxed. Fatigue that results from work demands greater than available time to complete them should be addressed with practice leadership to adjust and balance expectations.

There is no simple solution to the problem of hindrance. For the tasks that don’t require medical school and residency, it takes direct, respectful and solution-seeking discussions with leadership. A physician who expresses concerns with process and makes suggestions gets to be part of the solution.

Other Ideas

As for the seemingly endless minor hindrances throughout the work day, there’s a simple approach that’s illustrated by the current version of the well-known Serenity Prayer:18

“God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

No deity needs to be included; simply focus the prayer inward.

Eliminating or simply ignoring insignificant encumbrances likely will result in spontaneous stress relief. Actual relief can be attained by refraining from focusing on annoyances one cannot correct. One essential aspect of the management of hindrances as a cause of burnout is to recognize that medicine is no longer a hierarchical institution. We must allow physicians to grieve what was and accept what is. The practice of medicine in the 21st century is based on externally controlled, team-based and survey-based realities.

There are several tactics to combat the frustration of perceived deficient performance. The primary one is to improve efficiency and performance. This can be accomplished by taking advantage of automation, technology and the care team.

Leverage your EMR system by using pre-populated phrases, sentences and paragraphs to quickly document recurring clinical conditions, telephone interactions, recommendations, orders and advice. Also, create workflows that allow support staff to interact with patients and document aspects of care delivery as allowable by their training, certification and licensure.

Also, learn about the patient survey measures and physician comparison data. Use these results as feedback to adjust your communication, performance, teamwork and documentation. Remember that this feeling of unsatisfactory performance may be real or perceived. Physicians need to accept constructive feedback and use it to improve. As physicians, we need to remain dedicated to our patients and our profession, but we must be able to forgive ourselves if we are not invincible or perfect.

Finally, if withdrawal occurs and burnout is nearing completion, all is not lost. This is a protective escape. It is a result of feeling you’re not performing to self-expectations. Again, recognition of the condition is the first step in resolution. Address the steps highlighted above.

Conclusions

Despite these interventions and others, there are times when burnout is inevitable. In these cases, a clinical physician must plan an alternative position. Change can be as simple as changing geography or as dramatic as changing careers or retiring. But before making any change, it’s vital to make a serious and disciplined review of the pros and cons. This should be carried out with the support of a partner or friend for additional perspective. The adage about “the devil you know” should be kept in mind.

Burnout is common, inclusive of chronic exhaustion and negative attitudes toward work and self, affecting a significant number of physicians (and others) at all stages of their careers. It is a consequence of an excessively driven, high-performing, competitive and perfectionistic personality. Physician burnout has negative effects on job performance, patient care, personal well-being and employer success.

While burnout manifests in individuals, it is fundamentally a response to organizational culture and work life. Ameliorating its symptoms is not simple, but organization-directed interventions have demonstrated greater effectiveness than physician-based interventions in reducing burnout, which is a reaction to a series of stressors: fatigue, hindrance, frustration and withdrawal. Recognition of, and willingness to address, these stressors will allow individuals to prevent or alleviate burnout.

Future research must focus on strategies to recognize burnout as it develops, effective and generalizable organizational and individual interventions to manage burnout, and, most important, strategies to prevent burnout before it begins to develop.

Michael H. Goodman, MD, MMM, is an associate professor and pediatrics department chair at Cooper Medical School of Rowan University in New Jersey. He also is medical director of the Cooper Children’s Regional Hospital and the Women’s and Children’s Institute at Cooper University Health Care.

Michele Berlinerblau, MD, is an adult psychiatrist with training in psychoanalysis. She practices in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

Freudenberger HJ. “The staff burnout syndrome in alternative institutions.” Psychother: Theory Res. Pract. 1975;12:72-83.

Freudenberger HJ. Burn-out: The High Cost of High Achievement. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, Doubleday & Co. Inc; 1980.

Shanafelt TD. “Enhancing meaning in work: a prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care.” JAMA 2009;302(12):1338-1340.

The Physician Foundation. 2016 Survey of America’s Physicians: Practice Patterns & Perspectives. physiciansfoundation.org/uploads/default/Biennial_Physician_Survey_2016.pdf . Accessed April 16, 2017.

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. “Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population.” Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. “A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms.” BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1), 264. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4153-7

Montgomery A. “The inevitability of physician burnout: implications for interventions.” Burn Res. 2014;1(1):50-56.

Lown N, Lewith G, Simon C, Peters D. “Resilience: what is it, why do we need it, and can it help us?” Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(639);e708-e710.

Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, et al. “A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: results from the Healthy Work Place study.” J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8);1105-1111.

Shapiro F. “Who wrote the Serenity Prayer?” Yale Alumni Magazine, July/August 2008. yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/2143 .

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ and Shanafelt TD. “Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Lancet. 2016; Nov 5;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. Epub 2016 Sep 28.

Drummond D. Stop Physician Burnout: What to do When Working Harder Isn't Working. Collinsville, MS: Heritage Press Publications; 2014.

Merriam-Webster, merriam-webster.com/dictionary/burnout. Accessed April 16, 2017.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB & Leiter MP. “Job burnout.” Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001;52:397-422.

Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. “Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205.

Bakker AB, Demerouti E and Sanz-Vergel AI. “Burnout and work engagement: JD-R approach.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2014;1:389-411.

Bakker AB and Costa PL. “Chronic job burnout and daily functioning: the theoretical analysis.” Burnout Research 2014;1:112-119.

Chesanow N. “Does the Hippocratic Oath promote burnout?” Medscape. March 29, 2017.

Topics

Healthcare Process

Quality Improvement

Motivate Others

Related

Navigating Your Fertility as a Woman in MedicinePhysician Leadership, Narrative Medicine, and StorytellingA Leader’s Framework for Decision MakingRecommended Reading

Motivations and Thinking Style

Navigating Your Fertility as a Woman in Medicine

Motivations and Thinking Style

Physician Leadership, Narrative Medicine, and Storytelling

Motivations and Thinking Style

A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making

Quality and Risk

Dealing With Stress