Abstract:

The medical staff leadership of Carroll Hospital, a medium-sized community hospital in central Maryland, sought a better method of conducting provider quality reviews to decrease a two-year-long backlog, simplify the process, increase accountability, and improve patient safety. This led to the complete transformation of the Medical Staff Quality Committee (MSQC), which is responsible for provider quality reviews. The medical staff used iterative design: a workflow in which the process is tested and evaluated repeatedly at different stages of design to eliminate flaws to improve the design over time. The result was an increase in the quality of care, a decrease in opportunities for improvement, and positive reviews by providers, board members, and administrators.

The sole hospital in Carroll County, Maryland, Carroll Hospital is part of LifeBridge Health. Founded in 1960, this not-for-profit facility has 169 inpatient beds, a 50,000 visits/year Emergency Department, 1,000 newborn deliveries/year, and about 550 credentialed medical staff members (450 physicians and 100 advance practice providers) in 38 medical specialties aligned in nine departments.(1)

The hospital’s medical staff leadership sought a better method of conducting peer reviews, which led to the transformation of the Medical Staff Quality Committee (MSQC), which is responsible for provider quality reviews. The MSQC changes occurred in three discrete but interconnected stages: (1) reformation of the medical staff clinical quality review process, (2) communication of the aggregated data and trends to the medical staff at large, and (3) establishment of standardized departmental Ongoing Provider Performance Evaluations (OPPEs), which The Joint Commission mandated in 2007 that accredited hospitals provide to ensure quality practitioner performance.(2)

These efforts yielded a greater collaboration and deepened the trust between the medical staff and governing body. Each step led to greater transparency, mutual understanding, and a culture of safety and justice.

The Problem and Operational Significance

By 2015, our hospital’s MSQC, which had served us well for many years, was unable to keep up with the volume of case reviews requested. It also had not taken advantage of opportunities to link its protocols and procedures with ongoing practice reviews, best practices, and the provider core competencies. The last were defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)(3) in 1999 and subsequently adopted by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and included into their Maintenance of Certification (MOC) programs.(4) They include practice-based learning and improvement, patient care, systems-based practice, medical knowledge, communication skills, and professionalism. The Joint Commission emphasized these measures in its 2007 Medical Staff Standards.(5)

Peer review had become uncoupled from periodic performance evaluation and operated in isolation from other hospital quality-improvement efforts. The quality and credentialing arms of the organized medical staff operated in silos. Recognizing the opportunity, medical staff leadership undertook a sweeping reform and issued a mandate to reduce the backlog, increase representation/participation of medical staff members, harmonize reviews with OPPEs and other quality processes, promote equity, better disseminate information, and increase involvement of the governing body.

These opportunities appear in the Strengths, Weaknesses, Threats, and Opportunities (SWOT) analysis that emerged during Medical Executive Committee (MEC) deliberations (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: SWOT analysis

The Previous Operational Process

Until 2015, the Carroll Hospital medical staff held a quality committee meeting once a month to review cases referred for suspicion of deviation from standard of care by a privileged member of the medical staff. At that time there were no defined inclusion criteria for a case to be referred or forwarded to the committee. A screening body first reviewed and processed the complaint, but it did not include a licensed and privileged provider. Ratings did not have objective criteria for scoring. The members of the review committee did not reflect the diversity of the medical staff.

Because the committee met only once a month and could get mired down in prolonged discussion about one case, the queue for cases to be reviewed by the committee swelled to two-year backlog. When finally presented to the medical executive committee for their review, many cases concluded in a recommendation that was moot because the provider in question had left the institution, a system process change had already been adopted, or other events and actions had eclipsed the recommendations of the committee.

To confuse matters, a member of hospital administration, the chief medical officer, acted as spokesman for the medical staff and presented the finding to the MEC and the board. It was clear that the medical staff did not fully own the process nor were they invested in the outcomes. When questioned, almost no member of the medical staff knew how cases were referred to the committee or how the conclusions were presented afterward. Likewise, providers could not identify which actions could be taken to advise, mentor, or surveil their colleagues who were found to have deviated from the standard of care.

There was a great deal of apprehension and misunderstanding of the role of the quality review process. Providers viewed the process as punitive rather than as a tool to improve quality of care. In short, providers found the medical staff quality process opaque at best and a potential threat to their privileges or careers at worst.

The Implemented Intervention

While the burgeoning backlog was the immediate concern, it became apparent that solving one problem granted the opportunity to address the others. This led to a rapid series of interventions that wound up recharacterizing the entire process and the composition of the committee. Each stage was discussed and vetted by the MEC and governing body before being adopted. Thus, changes were made iteratively.

Timeliness

Previously, cases went through a lengthy process before final adjudication: submission, initial screening, assignment, committee discussion, and presentation to the medical executive committee and board of directors. The backlog could exceed two years. Meanwhile, memories faded, opportunities for rapid improvements were lost, and the medical staff did not see an effective connection between quality surveillance and action. After a review of the workflows, we determined that some steps were extraneous, and providers had too much time to respond to inquiries.

Timeliness is critical for quality. The sooner an error, system obstacle, or improper process can be identified, the sooner it can be addressed and fewer patients will be placed at risk. Providers who can be counseled soon after an event have the episode fresh in mind and can incorporate counseling or other recommended remedies long before the event fades from memory.

We considered many options, but the most compelling choice was to double the size of the committee and divide it into two panels. That would allow for a meeting every two weeks and would increase by 100 percent the capacity of the MSQC process. Combined with better screening and new members who were committed to focused reviews, this increased capacity slashed the backlog from 140 cases to zero in less than a year.

Representation/Participation

Creating a second panel required a doubling of the number of medical staff members participating in the committee. This allowed us to broaden the representation of the medical staff so that MSQC more accurately reflected the demographics of the medical staff as a whole: specialty, affiliation (employed, contracted, independent), age, gender, and years on staff. This allowed for a wider perspective and for more voices to contribute.

The larger departments (medicine, surgery, emergency) have at least one member on each panel. The smaller departments (pathology, pediatrics) have at least one member on one panel. Reviewers from the same department as the provider being reviewed present the events and salient details of a case to be deliberated. They collect statements from the provider being reviewed as well as any other hospital staff involved in the case. The reviewer offers a recommendation regarding whether care was appropriate and, if not, where opportunities for improvement exist.

While members of the panel rely on the opinion of a peer specialist for matters of clinical expertise or procedural skill, all can render judgment about professionalism, responsiveness, documentation, decision making, and behavior. This also confers credibility on the committee as it more closely mirrored the medical staff membership at large.

By longstanding tradition, MSQC reviews and summaries were not presented to MEC and the governing body by a member of the medical staff, but by an administrator: the chief medical officer, who had no vote at MEC at the time and may have had an alternate opinion or recommendation from the version he presented as an agent of the medical staff. This uncoupled the roles and responsibilities of the medical staff.

The medical staff needed to take ownership over quality among its members. A provider is more receptive to the opinions and recommendations that arise from a body of peers rather than from an administrator. Likewise, the medical staff would take its role more seriously and coach, mentor, and guide medical staff members if representatives had a clearer understanding of the entirety of the process and were responsible for presenting the findings to the MEC and board.

We created the position of a quality officer. The quality officer, a physician who is an active member of the medical staff, presents the findings to the MEC and answers any questions. The administration no longer acts as the spokesperson or advocate for the medical staff in its own executive meeting. The quality officer also sits on the screening committee and has a role in selecting cases for further review. As a licensed provider and privileged member of the medical staff, this perspective is given great weight.

Harmonization with OPPEs and Other Quality Processes

Previously, cases made their way to the quality committee by rule of thumb or subjective criteria. To make the process uniform, able to withstand critique, and amenable for analysis, we needed to develop specific criteria for inclusion, and we elected to have those criteria reflect the core competencies of The Joint Commission/Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Not only does the committee review clinical acumen and procedural skill, but also communication, professionalism, and teamwork. We also devised a new rubric for ratings to move from the loose and subjective designations of “minor and major opportunity for improvement” to outcomes such as effects on patient condition and interventions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Updated rating form

The new process imposed a tighter timeline and more efficient operations:

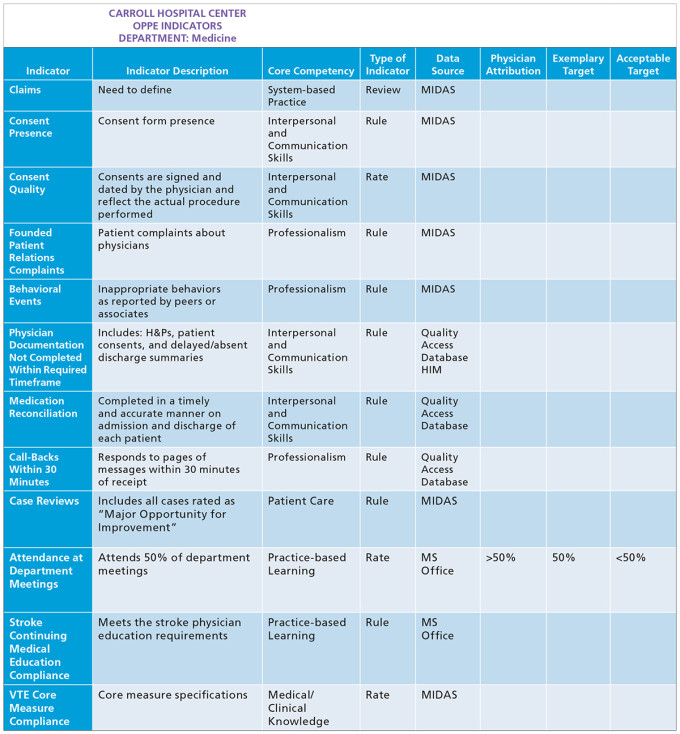

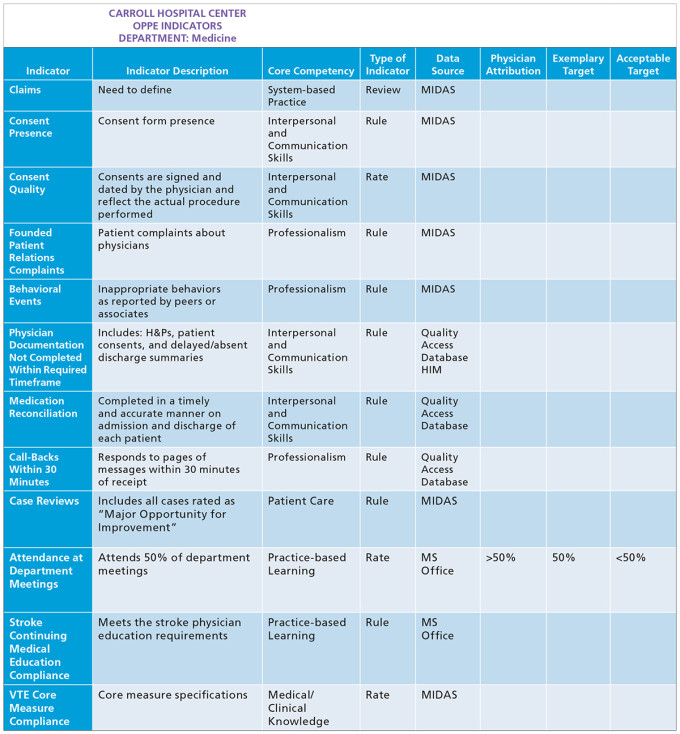

The clinical departments, through their chiefs, collaborate with the hospital department of quality and chief medical officer to jointly decide on review triggers. These may be rates-, rules-, or review-based and are predicated on the six core competencies defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and subsequently adopted by the American Board of Medical Specialties as a set of standards for maintaining a high level of quality care: Practice-Based Learning and Improvement, Patient Care and Procedural Skills, Systems-Based Practice, Medical Knowledge, Interpersonal and Communication Skills, and Professionalism. Figures 3 and 4 provide examples of review triggers from the departments of psychiatry and medicine.

Figure 3: Review triggers for department of psychiatry

Figure 4: Review triggers for department of medicine

The hospital quality department monitors provider and hospital quality data, as well as complaints from patients, payors, and staff, to identify cases for review.

Quality analysts from the hospital department of quality summarize cases, list findings of fact, and obtain statements from staff involved in the case.

One MSQC panel member, always in the same specialty as the provider being reviewed, is selected by the clinical quality officer to manage the presentation, proposing conclusions and recommendations for questions to ask the practitioner. If a case involves multiple specialties — for example, if the concerns about care spanned a patient’s journey from the emergency department to surgery to the critical care unit — then reviewers from each specialty coordinate their presentation of the case. Multiple providers may be reviewed and rated on a single case.

The case is reviewed by all MSQC panel members in advance.

At the MSQC meeting, the case is NOT re-hashed; it is settled or further input is sought.

The MSQC determines ratings and recommendations.

The findings communicated and improvement plans are created.

If care involves nursing or if there is a system issue that is beyond the control of the provider, the case is referred to Nursing Practice Review and/or to the safety and quality departments for root cause analyses or failure mode and effects analysis.

Our goal is for each case discussion to take 5–10 minutes. Our target turnaround time, from initial trigger to disposition, is less than 60 days.

OPPES

To encourage department chiefs to regularly update OPPEs as required by The Joint Commission (TJC) and become familiar with the practice of care by their members, each chief must present anonymized and composited data for their entire department twice a year. Statistics and trends reflect the rules, rates, and review indicators for the core competencies previously agreed upon by the chief, CMO, and quality department.

This not only makes the chiefs accountable to their peers, but also familiarizes them with their own data and allows other members of the medical staff to learn more about a department not their own. The outside perspectives prove valuable as comments and insights are offered from individuals with no inherent bias or interest.

These reports are forwarded to the MEC and Medical Committee for review. Chiefs take pride in presenting their data and are eager to show improving trends for safety and quality as well as the granularity and accuracy of the data. This was identified as a best practice on our last TJC survey.

Equity

In the rare cases when there is a concern for conflict of interest or a high likelihood for litigation, cases may be sent for an external review as well, but the panel will still deliberate and make its findings and recommendations known to the MEC.

An appeals committee was created such that if a provider disagrees with a rating, a second body can review the case. In all matters, the Medical Executive Committee renders a judgment and then passes the matter on to the Quality Committee of the board of directors for a final decision.

Dissemination of Information

Because the panels are composed of 25 members of the medical staff (about 10 percent of the active medical staff) and represent every department, the successes are well known and medical staff members are confident that the proceedings are fair, deliberate, and objective. Composited and anonymized data are presented to the interdisciplinary quality committee (see Figure 5). This has the salutary effect of informing hospital staff that providers are held accountable and their practices are reviewed. This has not led to an increase in cases reported for review.

Figure 5: Composited one-year results of the MSQC by department

Governance Changes

For the next step, which took a few years to complete, we combined the meetings of the Medical Executive Committee and the Quality Committee of the board (governing body). These meetings had been on separate days, about a week apart. Only a few members of the board were present at MEC meetings. Once the meetings were combined, all the members attended. As a condition of participation, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services require that the medical staff is accountable to the governing body for the quality of care provided to patients. The MEC is required to administer continuing surveillance of the professional performance of all individuals in the department who have delineated clinical privileges.(7) While the governing body is ultimately responsible for the quality and safety of care at the hospital, the governing body, medical staff, and administration collaborate to provide safe, quality care.

There were several reasons to combine the separate meetings into one:

About 90 percent of the same material had been presented at each meeting.

Only one set of minutes is required.

More board members can attend the MEC meeting and hear firsthand the discussions; they no longer need to rely solely on minutes and reminiscences of others.

Better bonding of and understanding among board members and MEC members is facilitated.

Reduces time to credential and privilege providers and take action on rules, bylaws changes, policies, and quality reports.

About 90–120 minutes of meeting time is cut from the schedules of executives, physician leaders, and board members, thus also saving money in otherwise lost revenue-generating hours.

The final step, not directly related to the MSQC process, was for the full board to grant final privileging action to the Quality Committee. In routine, noncontroversial cases — about 98 percent of the time — the final approval could be granted right after the combined meeting. This sped up the process by about five weeks, increasing our revenue by setting up providers for insurer credentialing much sooner.

A Concise Description of Results

After we had undertaken the reforms to our process, we saw a quick resolution of the backlog, increased medical staff participation, greater representation from multiple demographics, and a better understanding of the process and its goals from the governing body and the medical staff leadership.

Since our screening process was led by a physician, the process became more efficient at triaging out cases that had no opportunity for improvement; only cases that required deliberation made their way to the panels.

In 2014, 147 cases were sent for review (contributing to the backlog) and the committee decided that 80 percent had no identified opportunity for improvement. In 2015, 90 cases made their way out of screening for full deliberation (see Figures 6 and 7). Of those, 50 percent had opportunities for improvement identified.

Figure 6: Number of cases reviewed before and after reform of the Medical Staff Quality Committee

Figure 7: Comparison of ratings before and after reform of the Medical Staff Quality Committee

Because there were two panels, each case was afforded more time for discussion and backlogs were prevented. The panels spent their time and energy on cases that merited the consideration of the medical staff and warranted specific recommendations to improve safety and quality.

During the next few years, the medical staff and hospital staff became educated on which cases were appropriate to send for review. Consequently, more true positives and fewer true negatives made their way into the queue. Interestingly, approximately the same number of cases made their way from the screening committee to the review panels (~90/year) (see Figure 8). This allowed the panel to spend more time devising opportunities for improvement.

Figure 8: Trends in reviews over time

As the committee and panels matured, they identified more opportunities for system actions and referred cases to other hospital or departmental quality committees. These referrals were in addition to, not in lieu of, MSQC action (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Actions of the Medical Staff Quality Committee

A Concise Description of Operational Implications

The most salient features of the new process are the increased engagement of the medical staff and the unprecedented collaboration and mutual understanding between the medical staff executives and the governing body. Whereas only a fraction of the medical staff had any concept of the quality process before 2015, a significant segment of the hospital providers, especially those who are the most active, have an increased understanding. They are also more trusting of the process and are more likely to participate.

The entire quality committee of the governing body now attends the combined meeting. While only three board members may vote, all are free to pose questions, make comments, or ask for more information. There is no delay in transmission or diminution in the volume of information transmitted. This has further reduced the backlog, generated mutual trust and understanding, and inspired collegial thinking among medical executives and board members.

Since the department triggers and standards are rational and evidence based, the process is swift and transparent, and the entire management and governing team is unified, recommendations to improve quality, whether counseling and monitoring of providers or re-engineering other hospital processes have been strong and actionable. This has raised the bar for provider performance and has led to fewer providers on staff who conduct themselves outside of the expected standard.

The medical staff quality process dovetails with our credentialing and privileging activities. The software and metrics that surveil and guide the former generate data and reports for the latter, which is especially helpful during periodic recredentialing.

The MEC and board have expressed satisfaction and confidence in the process. It is swift, transparent, and has multiple checks and balances. It is fair for the providers reviewed and has multiple avenues for collaboration with other hospital committees (quality, nursing practice review, safety) so that best practices may be shared, or other reviews may be triggered as warranted.

A Concise Description for Next Steps

As more providers participate in the process and as they continue to gain confidence in the fairness and intentions of the efforts, they have suggested additional improvements. For example, providers wish to be notified immediately if one of their cases is being reviewed. If the initial screening panel determines that no deviation has occurred, the providers will receive letters that explain that finding and encourage them to continue their quality care.

We will begin to review cases identified as having excellent or exemplary care so that we may learn from them as models of practice. We will continue to review trends. All these data points are now pulled into a software program for OPPE/ FPPE developed at our hospital. This aids the department chiefs to respond to complaints, counsel providers, give the periodic feedback required by The Joint Commission.

We have engaged a biostatistician to review our outcomes and suggest how many cases need to be reviewed to yield the fewest false negatives and positives. At his suggestion we have randomly taken cases that scored “no opportunity” at the screening panel and sent them blindly to one of the review panels to test the accuracy of our screeners

References

Carroll Hospital. LifeBridge Health. https://www.carrollhospitalcenter.org/about-us . Accessed September 20, 2019.

The Joint Commission. Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation (OPPE) - Understanding the Requirements. https://www.jointcommission.org/standards/standard-faqs/critical-access-hospital/medical-staff-ms/000001500 . Accessed September 20, 2019.

NEJM Knowledge+ Team. Exploring the ACGME Core Competencies. NEJM Knowledge+. https://knowledgeplus.nejm.org/blog/exploring-acgme-core-competencies . Accessed September 20, 2019.

American Board of Medical Specialties. Based on Core Competencies. American Board of Medical Specialties. https://www.abms.org/board-certification/board-certification-standards/ . Accessed September 20, 2019.

Smallwood P. Using the JCAHO’s Six Competencies to Evaluate MD Performance. Hospitalist Management Advisor. October 1, 2006. https://www.hcpro.com/HOM-62362-3615/Using-the-JCAHOs-six-competencies-to-evaluate-MD-performance.html . Accessed September 20, 2019.

The Joint Commission. Revised Standards. The Joint Commission. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/MS_01_01_01.pdf . Accessed September 20, 2019.

Topics

Healthcare Process

Systems Awareness

People Management

Related

Sent Home To Heal, Patients Avoid Wait for Rehab Home BedsSelf-Defense in Medical Malpractice: How to Derail a Frivolous Malpractice LawsuitHow to Approach Business Ethics as Global Consensus Breaks Down