Abstract:

Authors explore the value of a structured, evidence-based curriculum to improve leadership behaviors in a hospital system across six clinician cohorts. They use specific leadership competencies and behaviors extracted from peer-reviewed literature and key stakeholder interviews to create the curriculum, and their findings indicate that strong physician leadership is a critical component in driving improved outcomes and quality of care for patients.

Health care organizations are becoming more complex as they expand into the full continuum of care. These shifts require new and emerging skills for clinician leaders. Enhancing the leadership skills of physicians and advanced practitioners — and preparing clinical leaders to move into roles as executives and directors — is essential to drive change, foster high reliability and improve patient outcomes.

Leaders must have the ability to inspire, influence, adapt and produce better outcomes. Better quality, higher patient satisfaction and elimination of unnecessary clinical variation to reduce costs require strong clinical leaders to increase efficiency and improve population health.(1) Historically, clinicians have moved into leadership positions based on their clinical skills, a combination of technical and evaluative skills resulting in their ability to deliver high-quality care. However, they often lack the interpersonal and leadership skills necessary to motivate and mobilize their colleagues and teams to work as an effective unit.

Medical education has changed recently, and while it includes training in the importance of teams coming together to care for patients, the mastery of clinical skills and knowledge often leaves no time for exposure to the principles of leadership.

Hartford HealthCare established its Physician Leadership Development Institute six years ago, in response to the need for more engaged and effective clinical leaders. Initially designed as a 10-month program with no tuition, the first class was composed of 32 physicians from a 74-applicant pool. The original curriculum was supported by an operating model called “How Hartford HealthCare Works” (or, H3W), which is the organization’s commitment to continuous improvement and a journey to a just culture. From the outset, PLDI was conceived to reinforce and train physicians in the context of the H3W operating model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. H3W operating model

The H3W model incorporates three components, approached in an orderly fashion:

Training in 10 H3W leadership behaviors (see Table 1).

Training in the principles of high reliability.

Exposure to, and training in, Lean management principles with a focus on daily management.

All leaders across the Hartford HealthCare system are required to uphold and model this approach.

To drive more-effective leadership, physicians must balance accountability, teamwork and autonomy. A component of the PLDI is the concept of team-based care. Research suggests a team-based approach can reduce medical errors, improve patient outcomes and add overall value to the culture of learning within a health care system.(2)

As Hartford HealthCare has grown and evolved in its cultural transformation, the PLDI has evolved with significant changes to the class composition, curriculum and assessments. The organization has welcomed advanced practitioners (nurse practitioners, nurse anesthetists and physician assistants) and has constructed an evidence-based curriculum that has a foundation of core leadership competencies.

From knowledge of the health care system, team-based care and emotional intelligence, the competencies and coursework are crafted to align strategic imperatives as an organization and the skills needed to be a successful leader. This supports the literature that physicians and advanced practitioners with higher emotional intelligence connect better with patients, exhibit more leadership qualities and foster enhanced teamwork, which leads to improved quality and safety outcomes.(3)

Methods

Applicants: Prospective physicians and advanced practitioners submit applications for the upcoming nine-month program over a rolling three-week period. All physicians and advanced practitioners from across the Hartford system are eligible to apply. In the past six years, there have been 343 applicants, and 197 have been accepted. Average class size is 32. For this discussion, we are focusing on the sixth cohort.

Core Competencies: An analysis was conducted on the available literature surrounding the elements of leadership characteristics. Focus areas included best practices from key clinical leaders and stakeholders, one-on-one interviews from both internal and external subject-matter experts, and core competency research.(4) We adapted the common themes found in the literature surrounding core leadership competencies to meet the needs of the PLDI cohorts and a revised curriculum. These core competencies were composed of key characteristics in management skills, strategic planning, knowledge of health care, problem-solving, emotional intelligence and communication. These domains were used to structure the overall curriculum to drive more meaningful engagement and improve the quality of the programming.

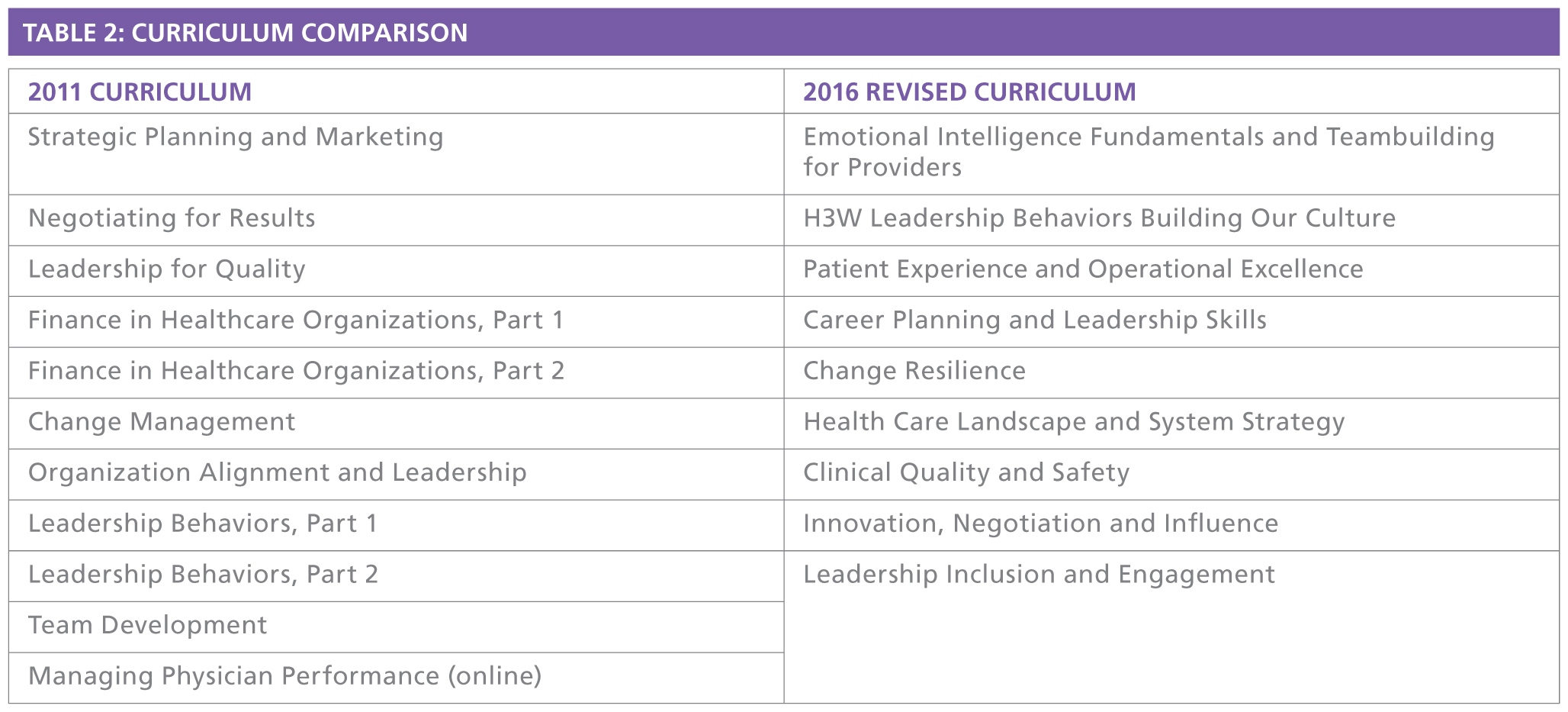

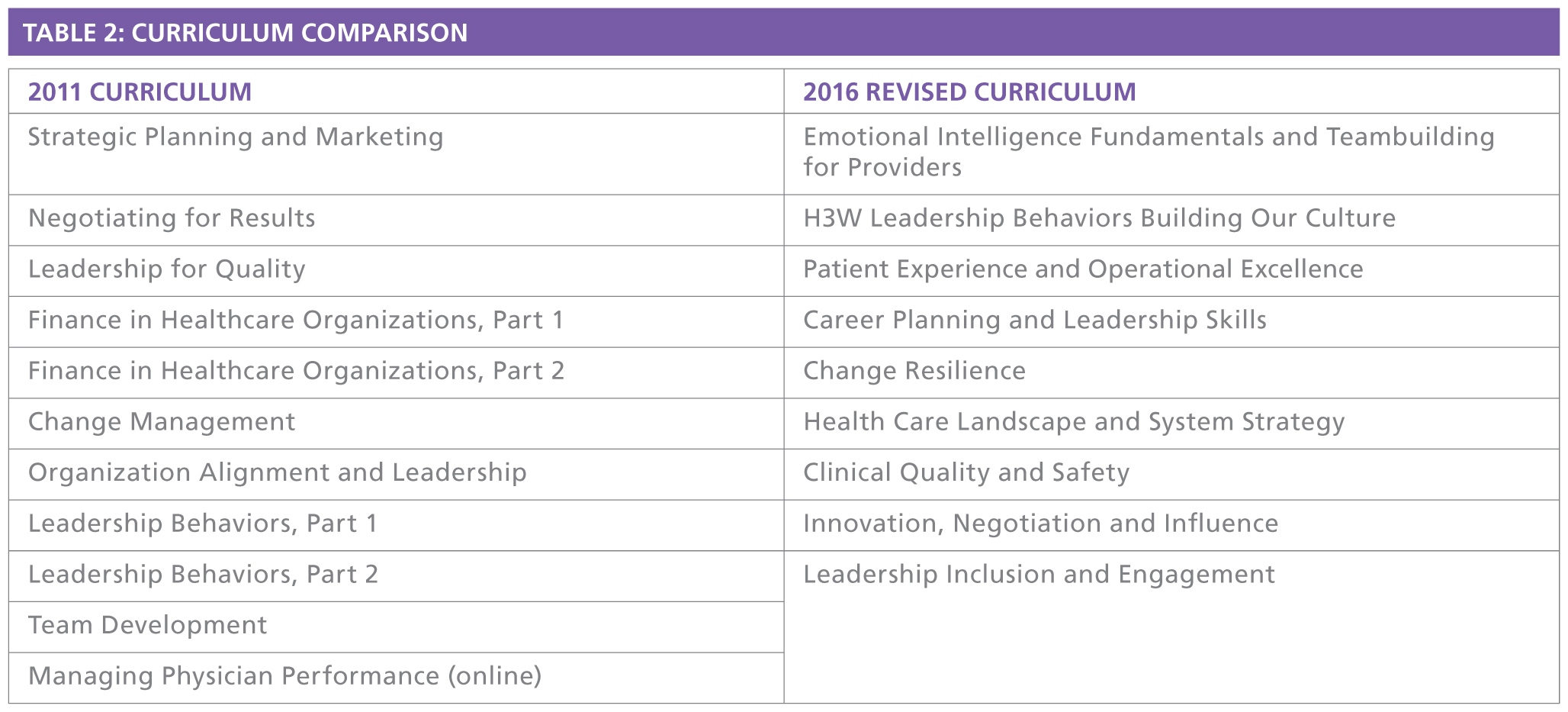

Curriculum: A revised curriculum and syllabus were created to support all of these core competencies with an emphasis on the behavioral attributes of leadership (see Table 2). Particular focus was placed on creating sessions that built upon each other to provide an all-encompassing framework of the Hartford system. In past cohorts, outside consultants provided primarily didactic lectures that were independent of each other. It left audiences wondering how the topics were connected, and, more important, how they were relevant to Hartford HealthCare’s culture and daily practice. In the revised curriculum, Hartford used its own subject-matter experts. Each session was built to support the previous one, in an effort to build a solid foundation and a robust leadership knowledge base. Participants were able to draw on previous sessions to reinforce lessons learned and bring those learnings into their daily leadership practices. Continuing medical education credits were provided for all sessions.

Assessments: Pre- and post-leadership competency, H3W Leadership Behaviors and program satisfaction assessments were administered electronically to participants in the sixth cohort.

Results

Participants rated the program experience an average 4.8 out of 5, based on five domains (see Figure 2). The group self-reported an improvement in confidence across the six competencies (see Figure 3), and a positive change in how they use the H3W Leadership Behaviors in their daily practice (see Figure 4).

Figure 2. Program experience assessment

Figure 3. Leadership competency assessment

Figure 4. Leadership behavior assessment

In addition, data was collated across all six cohorts to determine the number of participants promoted to a leadership position after completing the PLDI — 36 percent (see Figure 5). Less than 1 percent of physician promotions at Hartford HealthCare were received by nonparticipants.

Figure 5. Promotions received by PLDI participants across six cohorts

Discussion

For physicians and advance practitioners, education traditionally has focused on developing clinical competencies. Only recently have organizations begun to shift toward developing curricula for physicians that focus on interpersonal and communication skills in addition to professionalism. These are what the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education deems core competencies and desirable physician attributes.(5) These core competencies align with the leadership competencies Hartford HealthCare have developed.(6)

Organizations considering their own physician leadership programs must decide on the goals of the initiative. In the first years of the program, there was a greater focus on didactic education. Over time, Hartford shifted to emphasize leadership training and recognized that the acquisition of knowledge about finance, negotiations, strategy and marketing could be obtained in other venues. This evolution allowed Hartford HealthCare to focus the program on training in the organization’s operating model and the expected behaviors for its leaders.

A secondary benefit has been that recent PLDI cohorts have formed effective teams and developed relationships that have enabled participants to be successful in their primary roles. The PLDI “alumni” developed contacts in other regions and other clinical disciplines in the system, creating an informal network of leaders that now call upon each other for mutual support. Hartford HealthCare has attempted to maintain that spirit and connections with PLDI alumni events.

Another important lesson was setting the proper objectives for participants — at its inception, much of the PLDI was focused on remediation rather than transformation. Physicians unable to adapt to the new culture and demonstrate the H3W Leadership Behaviors were asked to leave the organization. These actions sent a clear signal to physicians that the new behavioral expectations in support of the culture were non-negotiable. Leadership is not about a title; it is about behavior. The entire competency-driven curriculum of the PLDI delivers evidence-based leadership qualities to improve interpersonal relationships, teamwork and collaboration, quality and safety, and, ultimately, the patient experience. Developing tools, strategies and education around leadership equips them with the means necessary to improve clinical care and quality outcomes.(6)

Evaluating the return on investment of a physician leadership program is challenging. Hartford HealthCare has noted the number of promotions participants have achieved. Correlating improved outcomes with participation in the program is more difficult. Program participants have been engaged in innumerable performance improvement initiatives, ranging from health system balanced-scorecard objectives to departmental improvement projects. The PLDI graduates have been involved in numerous successful initiatives, yet Hartford recognizes that proving that the program contributed to better outcomes is difficult.

Conclusions

Overall, the findings indicate a relationship between the education provided throughout the PLDI and the overall improvement in patient outcomes. In looking at Hartford HealthCare’s strategic imperatives and key performance indicators, it is important to note that many PLDI graduates are leading projects to improve the quality of care and patient outcomes for the system. They have been successful in leading systemwide quality initiatives. The data suggests the course curriculum is on track to address knowledge gaps throughout the system and deliver meaningful outcomes in support of the development of successful physician leaders.

The PLDI will help to blaze a trail for leaders, generating momentum for Hartford to reach its goal of being “most trusted for personalized coordinated care.” It also creates a pipeline of distinguished and reputable leaders to sustain the organization.(4)

References

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Triple Aim for Populations. 2017; http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx . Accessed Jan. 12, 2017.

Koles PG, Stolfi A, et al. The impact of team-based learning on medical students’ academic performance. Acad Med: J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2010;85(11):1739-45.

Stoller J, Goodall A, Baker A. Why the best hospitals are managed by doctors. Harvard Business Review, 2016; https://hbr.org/2016/12/why-the-best-hospitals-are-managed-by-doctors . Accessed Jan. 12, 2017.

Stoller JK. Developing physician-leaders: a call to action. J of Gen Int Med. 2009;24(7):876-8.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements. 2017; http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2017-2007-2001.pdf. Accessed Feb. 22, 2017.

Van Gorder M, Kearns D, Hong P. The need for physician leadership training: a survey of the American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology members. Phys Leadersh J. 2015;2(2):70-5.

Topics

Environmental Influences

Performance

Related

The Pandemic Proved That Remote Leadership WorksAmid Plummeting Diversity at Medical Schools, a Warning of DEI Crackdown’s ‘Chilling Effect’How Classical Hematology Aims to Meet the Growing Healthcare Needs of an Aging American PopulationRecommended Reading

Strategy and Innovation

The Pandemic Proved That Remote Leadership Works

Strategy and Innovation

Amid Plummeting Diversity at Medical Schools, a Warning of DEI Crackdown’s ‘Chilling Effect’

Strategy and Innovation

How Classical Hematology Aims to Meet the Growing Healthcare Needs of an Aging American Population

Strategy and Innovation

Dogs Paired With Providers at Hospitals Help Ease Staff and Patient Stress

Strategy and Innovation

Health Policy: What’s On the Table for the Second Trump Administration?

Strategy and Innovation

Mindbending Drugs: Psychedelics, Cannabis, and Physician Leadership