Medical gaslighting is a developing concept in healthcare that refers to the unintentional undermining or dismissing of a patient’s concerns or symptoms by healthcare providers. While this can lead to patient distress, misdiagnoses, and delays in treatment, the phenomenon is often not recognized by the physician involved.(1,2)

From the patient’s perspective, however, this dismissal erodes trust and can contribute to health disparities, especially among marginalized groups who are already facing discrimination in healthcare settings.

Although the medical literature on this issue is limited, its growing visibility through social media calls for physician leaders to understand its impact and take steps to reduce its occurrence. Addressing medical gaslighting requires a shift toward understanding how unconscious biases, communication challenges, and shared decision-making can affect patient care. By recognizing these dynamics, physician leaders can guide institutional culture toward more empathetic, inclusive, and patient-centered care.

Here, we discuss the intersection of medical gaslighting, the psychological principle of priming, and patient safety.(3,4) We also present practical strategies for physician leaders to implement that foster an environment of respect and collaboration with patients and ensure that both parties’ perspectives are valued.

WHAT IS MEDICAL GASLIGHTING?

Medical gaslighting refers to a situation whereby a healthcare provider may unknowingly dismiss, invalidate, or minimize a patient’s symptoms or concerns without a comprehensive investigation, often attributing them to psychological causes.(1,2) While the provider may not intend harm, the impact on the patient can be profound.(5–14) Dismissing a patient’s experience not only disrupts trust, but also may perpetuate health disparities, especially for marginalized groups who are already vulnerable to discrimination in healthcare settings.(1,2)

It is important to note that gaslighting in healthcare may not be intentional; physicians may be primed by their prior experiences, training, or unconscious biases that shape their perceptions and responses, sometimes leading to dismissive attitudes toward patients’ concerns.(15–20) Understanding that both the physician and patient bring complex histories and perspectives to the interaction can help mitigate these dynamics and foster a more effective and empathetic clinical environment.(20,21)

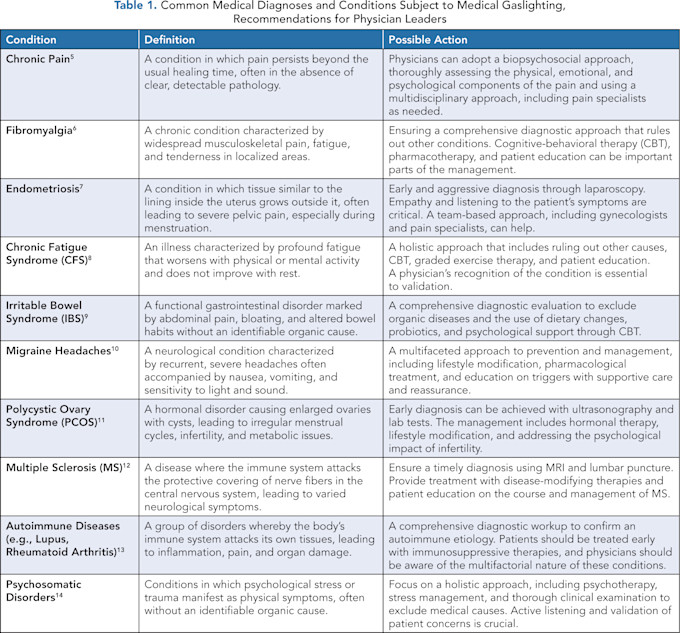

Table 1 highlights common conditions that are often subject to medical gaslighting and practical approaches to combat them. It includes relevant peer-reviewed references to guide physician leaders to additional reading and action.

THE PATIENT’S DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

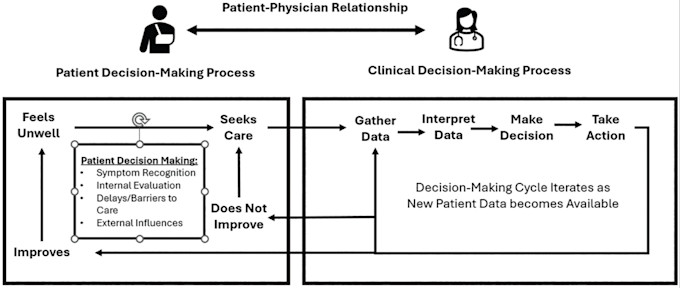

Understanding the dynamics of medical gaslighting involves considering the decision-making processes of both the patient and the physician (Figure 1). Patients make decisions about when to seek care based on their perceived symptoms as well as prior experiences with the healthcare system. They may evaluate their symptoms, seek the advice of friends and family, or investigate their symptoms through social media channels or the internet (Figure 1). The patient then decides whether the correct point of contact is their primary care provider, a specialist, or urgent or emergency care.

In their interactions with physicians, the patient must share information to help the provider address their concerns. Priming, where previous experiences influence decision-making, can significantly affect how patients present their symptoms and whether they feel validated by the provider’s response to their presentation.(4) This may be independent of the physician’s efforts or attempts to address the problem.

Figure 1. A Representation of the Patient and Physician’s Decision-Making Processes

Biases That Affect the Patient’s Process

When patients feel they are being medically gaslit, their perceptions are often shaped by various cognitive biases and psychological factors that can influence how they interpret their healthcare experiences.

Confirmation bias, where patients focus on evidence that supports their belief that something is wrong with their health while ignoring or discounting information that contradicts this view, is common. This bias can lead them to perceive a lack of empathy or acknowledgment from their doctor, even when the physician is struggling to make a definitive diagnosis.(22-24)

Another common bias is anchoring bias, in which patients become fixated on an initial diagnosis or idea about their condition, which shapes how they interpret subsequent interactions with healthcare providers.

If patients believe strongly that they have a particular condition, they may perceive every doctor’s response or test result as either validating or contradicting this belief, making it difficult for them to accept alternative explanations or be open to the uncertainty of a complex diagnosis.(24) This can lead to frustration or confusion, especially if they believe their concerns aren’t aligned with the medical explanations they are receiving.

A contemporary example is COVID-19.(25,26) Since the COVID-19 pandemic, an estimated 30% of patients who present with vague yet persistent physical concerns that impair their quality of life don’t get appropriately diagnosed.(25,26) In a population-based French study that investigated a wide range of patient complaints in a cohort of nearly 27,000 individuals, only persistent anosmia was positively associated with a positive serologic result.(25) Even for patients who attributed their symptoms to COVID-19 infection, there was no significant association between that belief and a positive serology of COVID-19.(25)

When COVID-19 symptoms were investigated in detail and compared to fibromyalgia (FM) and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), COVID-19 patients tended to report more symptoms than the general population, but often experienced less severe fatigue than those with CFS and less severe pain than those with FM.(26)

Emotional reasoning also plays a significant role. Patients may rely on how they feel emotionally to determine the reality of their physical condition. If they feel frustrated, scared, or in pain, they may assume that these emotions accurately reflect their health status, even if there is no clear medical explanation for their symptoms. This can lead them to believe their concerns are minimized or dismissed, even if the healthcare provider is following appropriate diagnostic procedures.(27-29)

Additionally, patients may experience catastrophizing, a cognitive distortion in which they magnify their symptoms and fear the worst-case scenario. This tendency can make them hyper-aware of minor bodily sensations, interpreting them as evidence of a serious condition even when their symptoms are benign. Catastrophizing can create a cycle of anxiety such that the patient is more likely to feel dismissed or misunderstood when a healthcare provider rightly reassures them that there is no serious underlying issue.(29)

Finally, a history of previous negative healthcare experiences can shape a patient’s perceptions. A patient who has been dismissed previously may approach future medical encounters with a heightened sense of mistrust or suspicion, anticipating the same outcome. This history can influence how they interpret interactions with healthcare providers, making them more likely to perceive a lack of attention or concern, even without any real dismissiveness. This cumulative effect of past experiences, coupled with cognitive biases, can make patients feel gaslit, even when there is no intentional invalidation of their concerns.(29)

THE PHYSICIAN’S DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

On the physician’s side, decision-making begins as soon as they enter a patient’s room.(16) The initial data, such as the reason for the visit or chief complaint, influences the physician’s clinical approach. The physician then gathers additional data, interprets the data, makes an assessment, and takes appropriate action by creating a plan and prescribing further diagnostic testing or treatments based on the findings.(21) The results of this interaction will lead to the patient’s concerns being addressed or not (Figure 1).(21)

Biases That Can Affect the Physician’s Process

Cognitive biases can be operative on the physician’s side as well, and affect the way that physicians engage with the patient’s clinical complaint. Physician bias can operate in the context of medical gaslighting in three ways.

The first way is implicit bias, a natural inclination to be for or against an idea based on prior experiences and learning. For example, physicians may be unconsciously primed to dismiss symptoms in certain patient groups.(3,16–18) The literature highlights several important disparities in care among women, minorities, and those of lower socioeconomic status, all of whom can also have a higher incidence of medical gaslighting.

Second, anchoring bias is a specific type of bias that occurs when a physician is primed by a patient’s initial symptoms or medical history and then anchors a diagnosis to the presenting symptom. For example, the chief complaint in the emergency department or at admission or in the outpatient environment may establish the reason for the patient’s visit. This may prime the physician to focus on that possibility, disregarding other medical conditions, even when the patient’s symptoms evolve or do not entirely fit with that initial complaint.

Finally, framing, which is the way a patient’s condition is presented by the patient or by a referring provider, can prime a physician’s response to treat the patient’s concerns with differing levels of credibility.

While these implicit biases may cause physicians to unintentionally dismiss the concerns of certain patient groups, potentially leading to medical gaslighting, no data currently support that assertion.(3,16,18,30,31) To date, much of the implicit bias work has focused on the major categories of race, gender, and socioeconomic status.(30)

This is important because implicit bias is a real phenomenon and mandatory training programs for physicians and other providers have exploded over the last decade.(30) However, the tools used to measure implicit bias and the programs created to address them are largely focused on the categories of race, gender, and socioeconomic status. Without further study, they cannot be directly extrapolated to medical gaslighting.(3,16,19,30,31)

It is also important to recognize that priming is not always negative; it can also enhance decision-making when physicians have positive prior experiences or when their training supports objective, patient-centered care. Primed responses are more accessible and accelerate certain determination, such as knowing the responses to an unresponsive patient are airway, breathing, circulation, or the dosage of a critical drug.

Physician leaders can mitigate the negative effects of priming by fostering an environment that promotes awareness of biases, reflective practices, and a commitment to treating all patients with respect and attention to their unique needs.

The perspectives of both the patient and physician play important roles in the outcomes of these interactions. Some patients will improve but feel unwell again and repeat the process from the beginning. Other patients will not begin to feel well and will continue seeking care. With each encounter, there is an opportunity for a new outcome. The patient and physician both have the prior visits’ data and personal experiences that allow them to make process changes for these subsequent encounters.

When medical gaslighting occurs, any of the decision-making steps on the patient’s or physician’s side become compromised. The patient may leave the encounter dissatisfied, with a delay in diagnosis, or an adverse outcome. The physician may have contributed to a misdiagnosis, delay, or unpleasant encounter.

It is also important to note that some patient conditions are complex and may require months to years before a diagnosis can be made. While this can be frustrating for patients, it does not mean that the physician has done anything incorrectly; nor does it mean that the physician was dismissive of the patients or their concerns.

MEDICAL GASLIGHTING AND PATIENT SAFETY

The consequences of medical gaslighting on patient safety can be serious, as it can contribute to diagnostic errors, delays in treatment, and unnecessary suffering.(18) Physicians risk underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis by not fully acknowledging a patient’s symptoms,(18–21) which can delay appropriate care and worsen the patient’s condition.

It is important to recognize, however, that physicians also face pressures and challenges, such as time constraints and cognitive overload, that can unintentionally influence clinical decision-making.(16,22) In these situations, it is crucial for the physician and patient to engage in open, honest communication. By creating a collaborative environment where both parties are encouraged to share their perspectives, medical errors can be minimized, and patient safety can be enhanced.

The consequences of medical gaslighting extend beyond diagnostic and medication errors to include communication failures.(18–22) Effective communication between physicians, patients, and the broader healthcare team is critical to patient safety.

When a physician dismisses or invalidates a patient’s concerns, the patient may feel unheard, resulting in frustration, mistrust, and disengagement from their care. Patients may withhold important information about their symptoms or fail to follow prescribed treatment plans. In some cases, patients may even seek care elsewhere, leading to discontinuity of care and potential gaps in treatment.(18,21)

Additionally, when physicians fail to communicate openly with colleagues, essential information may not be shared, leading to inconsistent or conflicting care plans. This communication breakdown can lead to preventable complications, delayed interventions, and ultimately, poorer patient outcomes.

INTERVENTIONS TO COMBAT MEDICAL GASLIGHTING

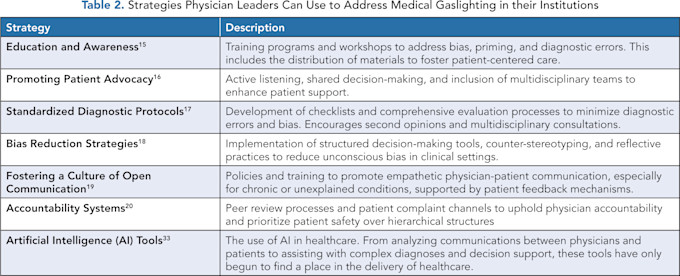

Physician leaders can implement evidence-based strategies aimed at individual clinicians and organizational culture to reduce medical gaslighting (Table 2).

A Biopsychosocial Model

A biopsychosocial model offers a comprehensive approach to addressing medical gaslighting by recognizing the interconnectedness of biological, psychological, and social factors in health.(32) This model emphasizes that medical conditions are not solely biological but are influenced by mental health, emotions, beliefs, and social contexts.(32)

Considering the whole person encourages healthcare providers to listen to patients’ experiences, validate their concerns, and engage in collaborative decision-making. This can counteract gaslighting behaviors where patients’ symptoms or concerns are dismissed, helping to ensure that patients feel heard, respected, and supported, ultimately fostering better trust and more effective treatment outcomes.

By fostering a culture that prioritizes open communication, mutual respect, and shared decision-making, physician leaders can use various strategies in their institutions to address the challenges medical gaslighting poses and improve patient safety. These strategies address biases and diagnostic errors and foster a more empathetic, patient-centered care environment.

Education and Awareness

Physician leaders can implement training programs and workshops that address implicit bias, diagnostic errors, and cognitive biases in clinical practice. These programs can help healthcare professionals recognize their potential for unconscious bias and improve their ability to provide equitable care. For further reading, see Chapman, et al., on implicit bias in healthcare professionals(15) and Hagiwara, et al., for a systematic review of implicit bias training.(30) Unfortunately, these programs are usually targeted toward implicit bias in race/ethnicity, sexuality, and disability. Their effectiveness may be variable and their impact on reducing the target behaviors is questionable for medical gaslighting.(23,30)

Promoting Patient Advocacy

Encouraging active listening and shared decision-making is essential for ensuring that patients feel heard and validated in their healthcare encounters. By involving multidisciplinary teams, physician leaders can create a supportive environment for patients, particularly those with chronic or unexplained conditions, reducing feelings of gaslighting.

Additionally, promoting collaborative care plans ensures patients’ voices are included in decision-making. For more information, refer to Mauksch, et al., on engaging patients in collaborative care.(16)

Standardized Diagnostic Protocols

The development of standardized checklists and comprehensive evaluation processes minimizes diagnostic errors and biases. By encouraging second opinions and multidisciplinary consultations, physician leaders can ensure that patients are thoroughly evaluated, reducing the risk of dismissing important symptoms. Implementing these protocols leads to more accurate and inclusive diagnoses. Croskerry provides a deeper dive into minimizing diagnostic errors.(17)

Bias Reduction Strategies

Implementing structured decision-making tools and reflective practices can significantly reduce unconscious bias in clinical settings. Physician leaders can also promote counter-stereotyping techniques to prevent biases influencing patient care. By addressing implicit biases, these strategies create a more equitable healthcare environment and ensure that all patients are treated with the respect and seriousness they deserve. FitzGerald and Hurst discuss strategies for reducing implicit bias in healthcare professionals(18) and Maina and Hagiwara provide alternative explanations regarding the impact of such tools.(30,31)

Fostering a Culture of Open Communication

Physician leaders should create policies and training programs that promote empathetic physician-patient communication, particularly for patients with chronic or unexplained conditions. Incorporating patient feedback mechanisms helps healthcare providers better understand patient concerns, reducing the risk of patients feeling dismissed.

A transparent, empathetic communication approach helps ensure patients are fully involved in their care decisions. Levinson, et al., emphasize the relationship between physician-patient communication and malpractice claims.(19)

Accountability Systems

Establishing peer review processes and patient complaint channels ensures physicians are held accountable for their actions, prioritizing patient safety over hierarchical structures. This approach addresses instances in which gaslighting may occur, ensuring that any dismissive behavior is addressed and corrected. A culture of accountability helps maintain high standards of care and reduces the potential for harm to patients.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

Artificial intelligence tools offer the potential to analyze physician-patient communications, providing insights into potential biases or dismissive language. These tools also can assist with complex diagnoses and decision support, reducing the likelihood of overlooking important symptoms.

AI’s role in healthcare continues to expand, offering new avenues for improving diagnostic accuracy and communication. For more on the role of AI in patient care, see Garg, et al.(33)

By implementing these strategies, physician leaders can play a crucial role in addressing medical gaslighting and ensuring that all patients receive fair, transparent, and empathetic care.

CONCLUSION

Medical gaslighting is a significant issue, and it can jeopardize patient safety, contributing to diagnostic errors and delayed treatments. Physician leaders can reduce its impact through a shared commitment to empathetic, patient-centered care. By addressing unconscious biases, enhancing communication, and promoting a collaborative approach to healthcare, physicians and patients can work together to improve clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Physician leaders have a unique responsibility to foster a culture of respect, accountability, and transparency, ensuring that all patients feel heard, validated, and empowered to participate in their care. Through these efforts, the healthcare system can become safer, more equitable, and more compassionate.

References

Ng IKS, Tham SZL, et al. Medical Gaslighting: A New Colloquialism. Am J Med. 2024;137(10):10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.06.022 .

McManimen S, McClellan D, Stoothoff J, Gleason K, Jason LA. Dismissing Chronic Illness: A Qualitative Analysis of Negative Health Care Experiences. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40(3):241–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2018.1521811 .

Masters C, Robinson D, Faulkner S, Patterson E, McIlraith T, Ansari A. Addressing Biases in Patient Care with the 5Rs of Cultural Humility, A Clinician Coaching Tool. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(4):627-630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4814-y .

Smith CP. First, Do No Harm: Institutional Betrayal and Trust in Health Care Organizations. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:133-144. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S125885 .

Schrepf A, Maixner W, Fillingim R, et al. The Chronic Overlapping Pain Condition Screener. J Pain. 2024;25(1):265-272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2023.08.009 .

Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: A Clinical Review. JAMA. 2014;311(15):1547–1555. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.3266 .

Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789–1799. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5 .

Jason LA, Sunnquist M, Brown A, et al. Examining Case Definition Criteria for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. Fatigue Biomed Health Behav. 2014;2(1):40-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/21641846.2013.862993 .

Lacy BE, Pimentel M, Brenner DM, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(1):17-44. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036 .

Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Overuse of Acute Migraine Medications and Migraine Chronification. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(4):301-307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-009-0048-3 .

Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, et al. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(1):54–64. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1514916 .

Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the Clinical Course of Multiple Sclerosis: The 2013 Revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278–286. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000560 .

Aringer M, Brinks R, Dörner T, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)/American College of Rheumatology (ACR) SLE Classification Criteria Item Performance. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(6):775-781. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219373 .

Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically Unexplained Physical Symptoms, Anxiety, and Depression: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):528-533. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000075977.90337.e7 .

Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and Implicit Bias: How Doctors May Unwittingly Perpetuate Health Care Disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–1510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1 .

Mauksch L, Safford BH. Engaging Patients in Collaborative Care Plans. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(3):35-39.

Croskerry P. The Importance of Cognitive Errors in Diagnosis and Strategies to Minimize Them. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):775–780. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200308000-00003 .

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit Bias in Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8 .

Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, et al. Physician-Patient Communication: The Relationship wsith Malpractice Claims Among Primary Care Physicians and Surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553–559. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03540310051034 .

Bohmer RMJ. Fixing Healthcare on the Front Lines. Harv Bus Rev. 2010;88(4):62–69.

Farmer JS, Slonim AD. Bedside Diagnostic Ultrasound: Potential and Pitfalls. In: Levitov AB, Dallas AP, Slonim AD, eds. Bedside Ultrasonography in Clinical Medicine. New York: McGraw Hill; 2011.

Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011.

Nickerson RS. Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises. Rev Gen Psychol. 1998;2(2):175–220. https://doi.org/10.1037//1089-2680.2.2.175 .

Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science. 1974;185(4157):1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124 .

Matta J, Wiernik E, Robineau O, et al. Association of Self-Reported COVID-19 Infection and SARS-Cov-2 Serology Test Results with Persistent Physical Symptoms Among French Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(1):19–25. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6454 .

Haider S, Janowski AJ, Lesnak JB, et al. A Comparison of Pain, Fatigue, qnd Function Between Post-COVID-19 Condition, Fibromyalgia, qnd Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Survey Study. Pain. 2023;164(2):385–401. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002711 .

Beck AT. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. New York: Penguin Publishers; 1979.

Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and Validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–532. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524 .

Johnson VE, Nadal KL, Sissoko DRG, King R. “It’s not in your head”: Gaslighting, ‘Splaining, Victim Blaming, and Other Harmful Reactions to Microaggressions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2021;16(5):1024-1036. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916211011963 .

Hagiwara N, Duffy C, Cyrus J, et al. The Nature and Validity of Implicit Bias Training for Health Care Providers and Trainees: A Systematic Review. Sci Adv. 2024;10(33):eado5957. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ado5957 .

Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, et al. A Decade of Studying Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias in Healthcare Providers Using the Implicit Association Test. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009 .

Engel GL. The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460 .

Garg RK, Urs VL, Agarwal AA, Chaudhary SK, Paliwal V, Kar SK. Exploring the Role of ChatGPT in Patient Care (Diagnosis and Treatment) and Medical Research: A Systematic Review. Health Promot Perspect. 2023;13(3):183–191. https://doi.org/10.34172/hpp.2023.22 .