Wall Street analysts evaluate the “margin expansion leverage” opportunities of target companies to determine financial performance potential and management’s abilities to exercise that leverage to increase bottom-line performance and company value. Margin expansion leverage (also known as margin leverage) often is characterized as management’s opportunities and abilities to improve financial performance by increasing operating margin, which generally is defined as the “gross margin yield.”(1)

Regardless of industry or business model, there are a limited number of “levers” available for leadership to pull to create margin expansion.

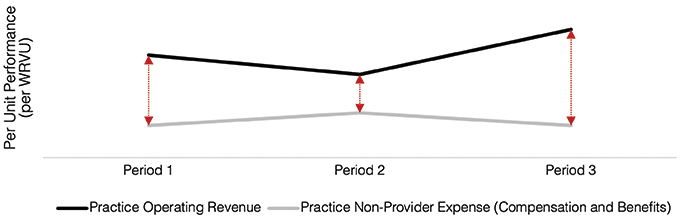

The principles of margin leverage performance management pertain to medical groups as well. Margin leverage is improved when operating revenue is increased per average unit of work effort produced by providers, with direct operating expenses associated with each provider work unit produced held to a lesser rate of increase. In the absence of margin leverage management, owners of medical practices can expect healthcare economic dynamics to cause operating cost inflation rate trajectories to degrade operating revenue gross profit performance, resulting in decreasing distributable net profit for owners of independent private practices (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Understanding the risk of deteriorating margin performance in a medical practice. The net operating revenue inflation rate is being overtaken by the operating expense inflation rate. The initial net effect is reduction of the owner compensation pool.

There are Only So Many Hours in a Day

It is no secret that health costs are under pressure. Macroeconomic dynamics are pressuring unit price, utilization, and total costs of care, especially for chronic disease management. Related dynamics extend to every facet of the healthcare delivery system, including the medical practice. Physicians reasonably lament the downward pressures on medical practice revenues while practice operating expenses increase every year, leaving practice owners with an ever-diminishing compensation pool.

A reality of the medical practice business model is that there are only so many hours in a day, and provider schedules have a limited number of appointment slots to fill. These two factors govern a practice business model’s clinical and financial productivity. The solution to the apparent conundrum is leveraged productivity leading to financial margin expansion. The challenge is finding and acting upon the potential.

Regardless of industry or business model, there are a limited number of “levers” available for leadership to pull to create margin expansion. Six rise to the top for consideration in most businesses. They are:

Pricing power: the ability to increase the unit price while holding all related direct operating expenses constant;

Unit production leverage: the ability to increase unit output production with effectively managed increases on attendant incremental operating expenses, variable and fixed;

Reductions of per-unit direct operating expense: reductions in some or all resource input requirements with unit production volumes and price held constant; simply reducing direct costs of providing a unit of clinical service and thereby creating improved operating efficiency;

Modifications of product and service offerings: the product or services mix is modified to favor higher margin products or services;

Strategic applications of short- and long-term debt: managed short- or long-term debt applications to specific products and services with higher margin expansion potential net of the costs of the debt applied; and

Redirecting target customer priorities: shifting brand and market positioning strategies to categories of goods or services that produce less price sensitivity and those that present more significant potential for long-term customer loyalty and repeat, cost-effective purchasing potential.

How Margin Leverage Applies to Medical Practice Strategies

Some physician leaders and practice administrators may reach this point in the article and argue that “medical practices are different; they don’t have the same business model flexibilities or potential to modify business models or methods to pursue margin expansion strategies. Missions, oaths to the professions, and obligations to communities necessarily restrict and constrain business strategy degrees of freedom.” If such an assertion is always true, then specialized medical group practices wouldn’t exist, small to medium-sized community hospitals could not make clinical programming decisions based upon their abilities to afford the attendant service line operating economics, and primary care clinics could not exercise professional prerogatives over patients they retain and treat versus those they refer out for care. The fact is that healthcare providers, especially private medical groups, can and should behave as any business would to pursue margin expansion strategies, with due consideration of organizational mission and the ethics of practice.

Figure 2. Evaluating the performance of margin expansion strategies in a medical practice. The relationship of per unit operating revenue to nonprovider operating expense (salary and wages) deteriorates from Period 1 to Period 2 and shows improved performance in Period 3.

Applications of Margin Leverage to Clinical Business Models in a Medical Practice

The following discussion of margin leverage model applies to a comprehensive, adult and pediatric medical and surgical eye care practice. At least one margin leverage tactic example is offered from the six-point generalized model.

Pricing power: Although third-party payers, commercial and governmental, continue to exert downward pressures on price, utilization, and total costs of care, upward of 72% of eye surgical care is for cataracts and is financed by Medicare. Medicare pays for a standard lens. With the standard lens, patients are not free from the need for glasses, and vision potential may not meet the needs or expectations of more active patients. There are alternatives to the standard lens, known as “lifestyle lenses,” which offer additional vision-related benefits. The price per lens implanted can be up to $4000 per eye, which the patient must pay out-of-pocket. When the advantages of these lenses are explained to the patient, they greatly prefer that option. Patients covered by Medicare Advantage plans are more likely to choose these lifestyle lens enhancements, because they can afford the out-of-pocket cost associated with their Advantage plans of choice. The implantation of lifestyle lenses increases the margin leverage of cataract surgery, even if the practice does not own a surgery center. The related out-of-pocket costs are typically billed along with the professional fee.

Unit productivity leverage: The opportunities for margin expansion offered here include the following four:

A medical group practice often demonstrates a variation of clinical services productivity between providers with similar direct operating expense structures (provider staffing costs, for example). Incremental productivity increases per provider typically are feasible with minimal expansion of direct operating expense and structures. The margin earned on incremental revenue productivity can be as much as 40%.

With clinical space availability, including expanded hours of service, incremental providers can be added with marginal increases in direct operating cost increases and minimal increases in indirect operating (overhead) costs.

In comprehensive eye care practices, the addition or expansion of optometry services permits increased profitability of routine and preventive services, freeing up ophthalmologist resources for allocation to more complex medical and surgical services.

The introduction or expansion of optical products offers opportunities to increase the financial returns per unit of provider productivity.

Reductions in “per unit” operating expense: Reductions in operating expense often are referred to as gains in operating efficiency, meaning with constant productivity and pricing, direct operating expense per unit of service “manufactured” is reduced. Such reductions can occur through service line innovations, the addition of facilitating technologies, and facility designs that enable enhanced operating efficiencies. Upward of 50% of every dollar of accrued efficiencies can drop to the bottom line for application to practice reinvestment or owner compensation.

Modifications and sizing of clinical service line portfolios: Medical practices are made up of varied clinical service lines and programs. Each carries a unique set of operating economics. For example, in a comprehensive eye practice, the operating economics of retina care differ from those of routine eye care. Likewise, the operating economics of adult and pediatric surgical services differ. Operating margin leverage within clinical service and programs is subject to shifts based on innovations in clinical care, commercial and governmental reimbursement policies, and capital asset investment requirements. When left unexamined and unattended by leadership, practices run the risk of clinical service portfolio ossification; unmanaged clinical services portfolios lead to deteriorating operating economics, producing declines in the actual financial performance of the practice. A practical, real-life example is a commercial payer who decides to reduce ambulatory surgical fees for cataracts by 30%. Why? Because they could. This shift in market dynamics reduces the margin performance of the surgical service component of the eye practice business model. Left unattended, the overall margin performance of the business model suffers. Given the growing demand for cataract surgery, the practice owners exercise a strategy to overcome the margin problem with expanded hours of surgical services, reduced surgical time per case, improved operating room turnover rates, increased implantations of lifestyle lenses, and improved management of resource input costs per case.

Strategic applications of short- and long-term debt: Unmanaged assumption of organizational debt is a governor of intelligent growth and margin leverage (e.g., a practice that borrows money to fund “unearned” compensation for practice owners is an inefficient and hazardous use of debt capacity). Managed debt, on the other hand, can be used effectively as a tool to facilitate margin expansion strategies. Key principles that guide uses of debt include investments that generate higher gross margin potential per invested dollar of debt, such as the addition of new providers; including employed versus additional practice partners; expansion of existing profitable clinical service lines and programs; facilities expansions to accommodate profitable growth; and the addition of profitable ancillary services.

Redirection of the target market and brand positioning strategies: For the comprehensive eye care business, upward of 65% of new patient business derives from well-crafted marketing and practice and provider promotion strategies, word-of-mouth recommendations, and referrals from external providers. Likewise, 30% of realized operating revenues can derive from out-of-pocket cash payments. These results are indicative of a medical specialty that has the potential to exert margin expansion leverage by way of market and brand repositioning strategies. The eye practice can redirect social media and current patient marketing campaigns to geographic markets with comparatively higher household incomes; strategically compatible demographic cohorts; eye health risk profiles with the need for more complex, higher-margin services, such as cataract surgery; and attractive optical product sales strategies.

Finding the Evidence for Margin Expansion Leverage in Practice Operating Economics Analytics

Although the ultimate test of margin expansion leverage progress in the private medical practice is the owners’ compensation pool growth, the conventional approach to practice accounting and reporting doesn’t sufficiently “zero in” on progress made with margin expansion tactics. Forward progress is better evidenced through operating economics performance analytics and reporting. Because such reporting methods are not customarily available from standardized computerized accounting packages, the practice described earlier customized an approach to analyze and report one key performance indicator (KPI) to demonstrate progress made by its margin expansion strategies. That KPI is displayed as the ongoing relationship between operating revenue (i.e., expected, accounted collections) generated per work relative value (WRVU) produced by all providers, compared with the average operating nonprovider human expense produced per WRVU. Results produced over nearly three years of chart production demonstrate a widening, positive gap in the relationship between operating revenue produced per WRVU and nonprovider human resource expense per WRVU; meaning the group is experiencing improving operating economic performance, per unit of provider production, even in the face of downward pressures on operating revenues and upward pressures on people costs, overall.

The reason for evaluating and reporting on this relationship is that nonprovider human resource cost is the largest single operating expense category for most medical practices.

The Role of the Physician Leader in Margin Leverage Strategies

Physician leaders have an essential role in successfully implementing margin expansion leverage strategies. By the very nature of their unique position within their practice, physician leaders must wear two hats: that of a revenue-producing provider and that of an administrator. For this reason, they are uniquely qualified to recognize which strategies are most likely to be successful and which are most likely to fail. They also recognize when an idea that may look appealing for purely financial reasons should not be undertaken for clinical or sometimes ethical ones. One example of a revenue-generating strategy that some eye practices employ is encouraging all patients to have retinal photographs taken. Although this technology may look good on paper—it is low cost to the patient and can bring incremental, profitable revenue to the practice—it has not gained widespread application because of its limited clinical usefulness.

Because they are providers as well as adminstrators, physician leaders should strongly understand the practice’s mission. They should be able to steer the company away from business decisions that do not adhere to this mission. One example of this from the last decade is the creation of hearing aid programs within eye care groups. Although pitched as a way to provide a needed service for the elderly patients already being seen by eye care providers, at its root, it was little more than a passive income stream for physician owners. Although it was successful in some practices, it failed in many because it did not align with the primary mission of most eye practices—to provide high-quality eye care to the communities they served.

Physician leaders are uniquely positioned to evaluate how decisions may affect their colleagues and ancillary staff teammates by being part of the care team.

Physician leaders also can model behavior more efficiently in ways that influence the culture of the practice. Ancillary staff look to the provider team for clues as to why certain decisions are made. Many staff members assume that the administrative team makes decisions with little input from the provider team. By being on both teams, the physician leader can assure the rest of the staff that the provider team has approved all decisions that affect patient care.

Physician leaders are uniquely positioned to evaluate how decisions may affect their colleagues and ancillary staff teammates by being part of the care team. One example of such a decision is extending business hours to increase early morning, evening, or weekend availability. Keeping the clinic open on a Monday when an observed holiday falls on a Tuesday is another. Both examples may be appealing when looked at from a purely financial standpoint. However, because physician leaders work alongside other providers and ancillary staff, they often recognize potential problems that these decisions may cause, such as increased burnout, childcare issues, worsening morale, and decreased engagement. In this way, physician leaders should have their “fingers on the pulse” in ways that nonclinical administrators may not.

Applying Lessons Learned: The Psychology of Managing the Opportunities for Margin

Healthcare providers, especially physicians in private practice, often feel trapped in an industry with deteriorating economics, leading to a perceived loss of control over professional freedoms and business development opportunities.(2,3) Although such perceptions are not entirely wrong-headed, opportunities to grow and develop a medical practice profitably remain available.

The principal challenge in applying margin expansion strategies was cited earlier as the risk of “ossification” of preferred business models. Medical practices are composites of individual professionals with preferred practice styles and production rates. The operating economics of each can be unique in financial performance and vulnerability to market dynamics. Finding a medical practice’s market expansion leverage potential often is easier than acting upon it. There is a psychology to managing margin expansion strategies. It begins with professionals concluding that the preferred practice model isn’t working—it’s on an economically entropic path, but the trend is reversible with planning and action. With acceptance, the group can move on to an examination of the margin expansion opportunities and, with action, improve the practice’s profitability while regaining a sense of control over the future of the practice.

References

Zismer DK. Clinical service line strategies in lifestyle medicine. In: Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, eds. Creating a Lifestyle Medicine Center from Concept to Clinical Practice. Springer Nature Switzerland, AG; 2020:65-77.

Zismer DK. Discussion: framework to gauge physician burnout. Physician Leadership Journal. 2019;6(3):50-54.

Zismer DK, Schwartz GS, Zismer ED. The tyranny of the practice overhead debate. J Med Pract Manage. 2022;38(1):17-19.